The creator is eternal, he who now controls

and holds this earth to its foundations.

The ruler is powerful and king by right,

the lone wielder of all, he holds and controls

5 earth and heaven, just as he encompasses about these things.

He wondrously created me in the beginning,

when he first built this world,

commanded me to remain watching for a long time,

so that I should not sleep ever after,

10 and sleep comes upon me suddenly,

my eyes are quickly shut.

The mighty lord controls in every respect

this middle-earth with his power;

just as I by the word of my leader

15 entirely enclose this globe.

I am so timid that a spectre quickly

travelling can frighten me fully,

and I am everywhere bolder

than a boar when he, enraged, makes a stand;

20 no standard-bearer in the world

can overpower me, except the one God

who holds and controls this high heaven.

I am in scent much stronger

than incense or rose are,

25 [a half-line is missing here] in the turf of the earth

agreeably grows; I am more delicate than she.

Although the lily is beloved to humankind,

bright in blossom, I am better than she;

likewise I necessarily overpower the nard’s scent

30 with my sweetness everywhere at all times,

and I am fouler than this dark fen

that stinks nastily here with its filth.

I rule all under the circuit of heaven,

just as the beloved father taught me in the beginning,

35 so that I might rule by right

the thick and thin; I hold the likeness

everywhere of everything.

Higher I am than heaven, the high-king commands me

secretly to behold his mysterious nature;

40 I also see all the impure, foul dens

of evil spirits under the earth.

I am much older than this world

or this middle-earth might become,

and I was born young yesterday

45 famous among humans through my mother’s womb.

I am fairer than treasure of gold,

though it be covered all over with wires;

I am more vile than this foul wood

or this sea-weed that lies cast up here.

50 I am broader everywhere than the earth,

and wider than this green plain;

a hand can seize me and three fingers

easily enclose me entirely.

I am harder and colder than the hard frost

55 the sword-grim rime, when it goes to the ground;

I am hotter than the fire of bright light

of Vulcan moving quickly on high.

I am yet sweeter in the mouth

than when you blend bee-bread with honey;

60 likewise I am harsher than wormwood is,

which stands here grey in the wood.

I can feast more mightily

and eat as much as an old giant,

and I can live happily forever

65 although I see no food ever again.

I can fly faster than a pernex

or an eagle or a hawk ever might;

there is no zephyr, that swift wind,

that can journey anywhere faster;

70 a snail is swifter than me, an earth-worm quicker

and the fen-turtle journeys faster;

the son of dung is speedier of step,

that which we call in words ‘weevil’.

I am much heavier than the grey stone

75 or a not-little lump of lead,

I am much lighter than this little insect

that walks here on the water with dry feet.

I am harder than the flint that forces this fire

from this strong, hard steel,

80 I am much softer than the downy-feather,

that blows about here in the air on the breeze.

I am broader everywhere than the earth

and wider than this green plain;

I easily encircle everything,

85 miraculously woven with wondrous skill.

There is no other creature under me

more powerful in this worldly life;

I am above all created things,

those that our ruler wrought,

90 he alone can increase my might,

subdue my strength, so that I do not swell up.

I am bigger and stronger than the great whale,

that beholds the bottom of the sea

with its dark countenance; I am stronger than he,

95 likewise I am less in my strength

than the hand-worm, which the children of warriors,

clever-minded men, dig out with a knife.

I do not have light locks on my head,

delicately wound, but I am bare far and wide;

100 nor might I enjoy eyelids nor eyebrows,

but the creator deprived me of all;

now wondrously wound locks

grow on my head, so that they might shine

on my shoulders most wondrously,

105 I am bigger and fatter than a fattened swine,

a swarthy boar, who lived joyfully

bellowing in a beech-wood, rooting away,

so that he … [a page is missing in the manuscript here at the end]

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 32

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Tue 23 Dec 2014Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 32

Hello, readers. Have you missed me? I’m sure that you have, but my need for validation means I just gotta ask. I’ve had a busy-busy term, and have been oh so very lucky that all sorts of lovely guest bloggers have turned up to entertain you. But now it’s the holidays, which means it’s my turn again.

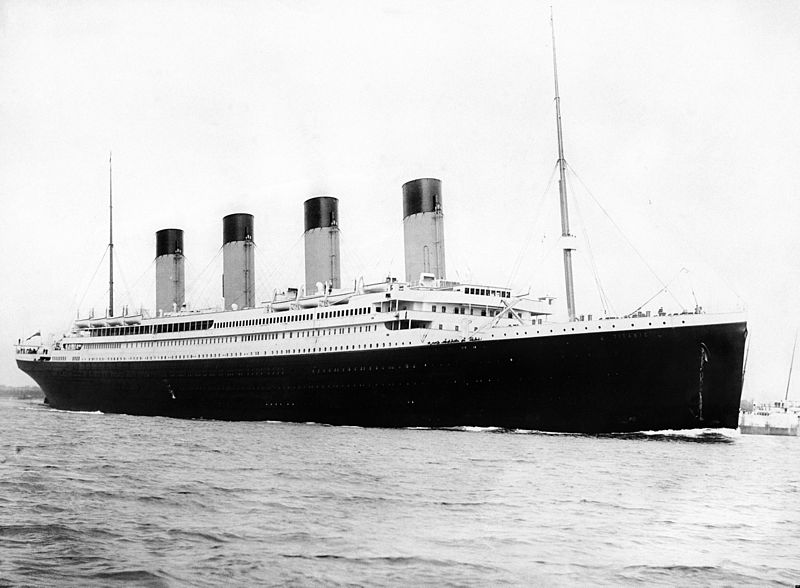

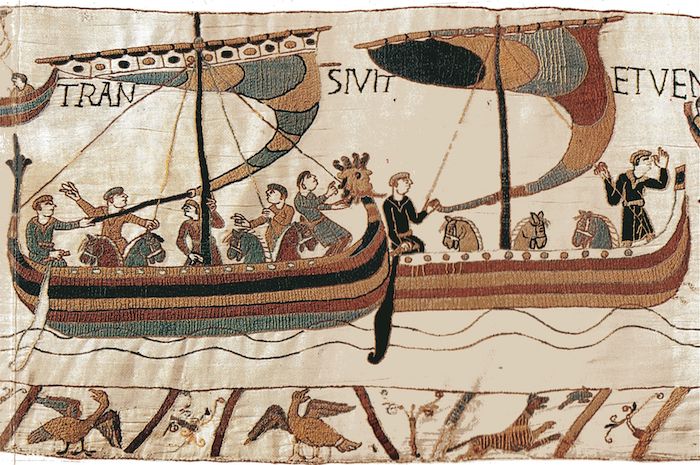

Let’s talk about ships.

But is the subject of Riddle 32 a ship? You are, perhaps, not convinced. There are other suggestions for the solution, which include Wagon, Millstone, Wheel and Wheelbarrow. Naturally, the library has none of the books I need to tell you all about the folks who suggested these things (it’s the holidays, so the library has already been pillaged from pillar to post by keen vacationers). However, I can tell you that Ship is a scholarly favourite. How’s about I explain why I like it and then you write in if you prefer one of the other readings? Yes, let’s do that.

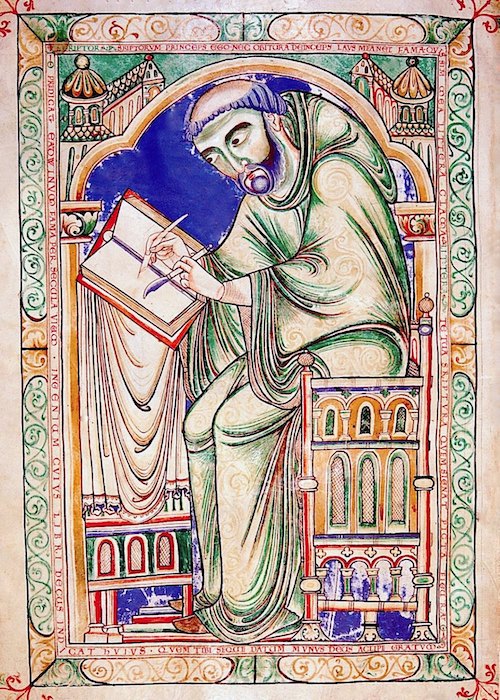

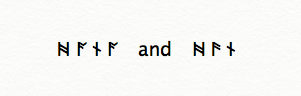

Right, so ships. The first thing I’ll say is that the screaming we see in line 4b (giellende) is quite a bird-like act. Huh? Let me rephrase: in other Old English poems, the verb gyllan (to scream/yell/call) is applied to the sounds of birds. So in Solomon and Saturn II, the strange, apocalyptic bird referred to as the Vasa Mortis gilleð geomorlice and his gyrn sefað (Anlezark, line 90 or ASPR, line 282) (calls miserably and mourns its misfortune). Equally, The Seafarer is marked by avian imagery when it describes the gifre ond grædig (eager and greedy) anfloga (lone-flier), which gielleð (calls) in line 62. Finally, Riddle 24’s magpie hwilum gielle swa hafoc (line 3b) (sometimes calls like a hawk). And, as we know from poems like Beowulf, ships are the giant manmade birds of the sea (write that in an essay…I dare you!). Hence, the poem refers to the flota famiheals fugle gelicost (line 218) (foamy-necked ship most like a bird) and the swanrad (line 200a) (swan-road), the latter of which is a kenning for the sea (also appearing in Andreas, line 196b). So, the sound that the subject of Riddle 32 makes gels with other Old English poetic approaches to ships.

Here’s the famous Norwegian Oseberg ship. Photo (by Uwe kils) from the Wikimedia Commons.

What about all that grinding? Surely grindan in line 4a could be better linked to a millstone, non? Well, yes, but that’s not to say that ships don’t also grind (best mental image ever: Old English dance-party…ships grinding to hiphop music…shocked monks looking on from the sidelines). In fact, in Guthlac B, we have almost the exact same half-line applied to a ship:

Lagumearg snyrede, gehlæsted to hyðe, þæt se hærnflota æfter sundplegan sondlond gespearn, grond wið greote. (1332b-5a)

(The sea-steed hastened, laden to the landing, so that the wave-floater after the swim-play perched upon the sandy land, ground against the grit.)

The half-line is again repeated in Andreas, as grund wið greote (line 425a). These three instances are the only times that grindan and greot are linked in Old English literature. So, what we can now see is clearly a poetic formula (a repeated, variable verse unit) – grindan wið greote – has clear shippy connotations. These aren’t the only formulas in Riddle 32: the opening and closing half-lines can be found in the riddle directly before this one in the manuscript. These poets know their shiz, man.

Anywho, the formulaic stuff I’ve just discussed has me convinced of the ship reading, although I recognize that faran ofer feldas (line 8a) (going over fields) is a better literal description of a wheelbarrow. To that I say: since when are riddles literal? Directly following this half-line, we have ribs, which are almost certainly not literal ribs. This metaphor could be applied to any rounded object, but I like the image of the ship’s wooden planks as the creature’s ribs.

It’s a bit blurry, but check out this model of the Sutton Hoo ship burial. Look ribby enough for you? Photo (by Steven J. Plunkett) from the Wikimedia Commons.

A ship is also a terribly cunning contraption that looks a heck of a lot like a giant foot (á la line 6b). Fact. So, I’m throwing my lot in with Ship.

If you want to know just what type of ship this might be, then look no further than lines 9b-13. Here, the poet tells us that the riddle-subject brings food and treasures (metaphorical or literal) to people rich and poor. This reference points to the use of ships as transport vessels for all things mercantile – hence Niles has solved the riddle in Old English as Ceap-scip (merchant ship) (page 141). The transportation of goods via waterways in early medieval England was common (Williamson, page 236). Katrin Thier talks about ships of various breeds and creeds in her article on nautical material culture, but…as with all the other books in the library, her article is currently unavailable to me.

Given the general library pillaging that has gone on up here in Durham, I can only conclude that it must be the holiday season! So, with that realization, I’m going to stop blogging at you and go eat some mince pies. May the ships of the holiday season bring you all an abundance of food and treasure! That’s a thing, right?

*hastily re-reads riddle to check whether it could in fact describe Santa’s sleigh*

References and Suggested Reading:

Anlezark, Daniel, ed. and trans. The Old English Dialogues of Solomon and Saturn. Anglo-Saxon Texts, vol. 7. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2009.

Niles, John D. Old English Enigmatic Poems and the Play of the Texts. Studies in the Early Middle Ages, vol. 13. Turnhout: Brepols, 2006.

Thier, Katrin. “Steep Vessel, High Horn-ship: Water Transport.” In The Material Culture of Daily Living in the Anglo-Saxon World. Edited by Maren Clegg Hyer and Gale R. Owen-Crocker. Exeter Studies in Medieval Europe. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2011, pages 49-72.

Williamson, Craig, ed. The Old English Riddles of The Exeter Book. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 32

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 24