Boniface Riddle 17: Ignorantia ait

NEVILLEMOGFORD

Date: Wed 28 Jul 2021Iam dudum nutrix errorum et stulta vocabar:

Germine nempe meo concrescunt pignora saeclis

Noxia peccati late per limina mundi,

Ob quod semper amavit me Germanica tellus,

5 Rustica gens hominum Sclaforum et Scythia dura.

Adsum si gnato, genitor non gaudet in illo.

Non caelum terramve, maris non aequora salsa

Tranantem solem et lunam, non sidera supra

Ignea contemplans quaero, quis conderet auctor.

10 Altrix me numquam docuit, sapientia quid sit.

Altera sordidior saeclis non cernitur usquam.

Idcirco invisam vocitat me Grecia prudens,

Tetrica quod numquam vitans peccamina curo.

For some time now, I have been called a dolt and the nursemaid of errors:

indeed, from my seed the guilty children of sin

spread widely in the world, to the ends of the earth,

because the German soil has always loved me,

5 the rustic tribe of the Slavs and hard Scythia.

If I am born, a father does not rejoice.

Gazing outwards, I do not ask what creator founded

the earth or sky, the sun and moon crossing

the salty surface of the sea, and the stars burning above.

10 A nursemaid never taught me what wisdom is.

No one filthier is seen anywhere on earth.

For that reason, the wise Greeks call me the unseen [or hated] one,

because I never try to run from terrible sins.

Notes:

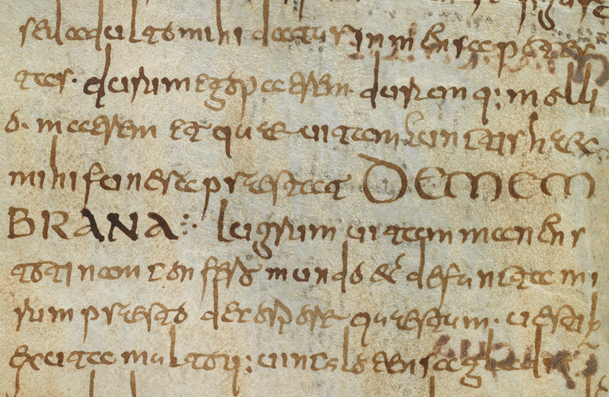

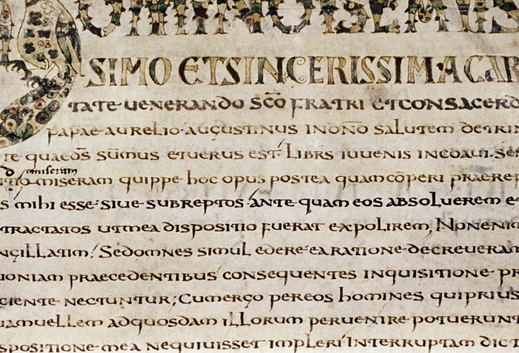

This edition is based on Ernst Dümmler, (ed.). Poetae Latini aevi Carolini, Volume 1. Berlin, MGH/Weidmann, 1881. Pages 1-15. Available online here.

Note that this riddle appears as No. 9 (De vitiis) in Glorie’s edition and 19 in Orchard’s edition.

Commentary for Bern Riddle 17: De cribro

NEVILLEMOGFORD

Date: Fri 22 Jan 2021Matching Riddle: Bern Riddle 17: De cribro

Sometimes riddle-reading can be very inten-sieve! Today’s riddle is about a sieve—not a kitchen sieve, but an agricultural one.

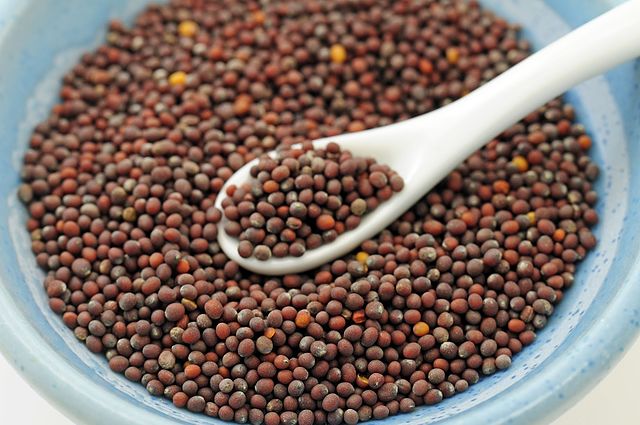

The opening two lines of this riddle are a great example of riddling disguise and misdirection, describing the sieve as if it were a loquacious Mr Ed. Line 1 explains that the riddle creature’s mouth that is always open and the lips that are never sealed—a quality of both sieves and talkative people. Line 2 goes on to describe how the creature is urged on its cursus (“course”) by frequenti verbere (“a well-used whip” or “a frequent blow”). It describes the act of shaking the sieve as if it were the whipping of a horse, which recalls the eccentric horse-bench of Riddle 4. The material that is being sieved is probably flour—made with Riddle 12’s grain and Riddle 9’s millstone—which is being separated from any bran or other impurities and made finer for baking.

The sieve begins to come into focus in line 3, which tells us that the object has no exta (“insides, bowels”) unless they are placed in there by hand, referring to its concave nature. The riddle then describes sieving as a violent act—the minutum vulnus (“tiny wound[s]”) represents the sieve’s holes, and the moving is the act of sieving.

The last two lines were not the easiest to translate, but the general idea is of separating good (i.e. the flour) from bad (i.e. the bran). This idea has distinctly a biblical feel, and I suspect that the author had Jesus’ remark to Simon Peter that Satan would sift the disciples like wheat (Luke 22.31). Whether he did or not, the central motif in this part of the riddle is that the sieve, who is left with only the detritus, gets the worst of the deal. Even worse, he is then abandoned, having served his purpose. What a sad ending for the poor sieve!

Related Posts:

Bern Riddle 4: De scamno

Bern Riddle 9: De mola

Bern Riddle 12: De grano