Commentary for Lorsch Riddle 10

NEVILLEMOGFORD

Date: Mon 21 Jun 2021Matching Riddle: Lorsch Riddle 10

Whoever would have thought that such a sunny riddle could also be so dark! This clever little riddle juxtaposes grim images of theft, murder and execution with splendid chapel lamps and the sun.

Lamps and other light sources are common riddling subjects. For example, Bern Riddle 2 is all about an oil lamp. The anonymous late antique riddler who is known to us as Symphosius (the name literally means “party-guy!”) wrote a riddle (No. 67) about a lantern. And the seventh century churchman and poet, Aldhelm of Malmesbury, wrote a riddle on the candle (No. 52). Today’s riddle describes a lamp used in a church, possibly a sanctuary lamp that was hung in front of the altar, as per the instruction of God to the Israelites to burn an oil lamp in the Tabernacle in Exodus 27:20-21.

”Sanctuary lamp from the Basílica de São Sebastião, Salvador, Brazil. Photo (by Paul R. Burley) from Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY-SA 4.0)”

The riddle begins with the lamp denying that it is a robber or a killer. Playing on the connection between night and criminality, it explains that, although it is up all night, it goes about its business in a completely-innocent-and-not-at-all-nefarious way. Yeah, sure, lamp—I believe you!

Line 3 then introduces a twist—the lamp hangs from the ceiling in laqueo… longo (“on a long noose”) as if it were an executed criminal. There were many crimes potentially punishable by death in early medieval England, including counterfeiting and treason, as well as robbery and theft. Archaeological evidence shows that decapitation was a common of execution, but hanging was also used, and several law codes refer to it. For example, in a supplementary code covering the administration of justice in London, King Æthelstan explains that hanging is appropriate for repeat thieves under the age of fifteen, if they have not kept the oath that they were forced to swear after their first offence:

Gif he þonne ofer þæt stalie, slea man hine oððe ho, swa man þa yldran aer dyde.

[If he then steals after that, he will be decapitated or hung, just as his elders will have been.]

–VI Æthelstan, 12.1 (page 183).

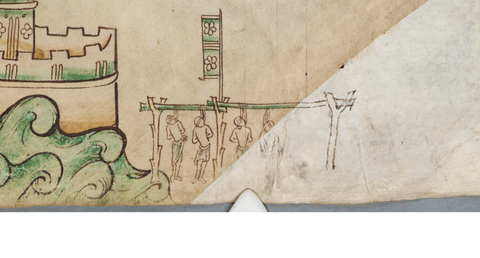

So, hanging was a fairly common punishment for crimes that we would consider to be minor today. Interestingly, a reference to hanging also appears in another riddle, Bern Riddle 57, which links the daily passage of the sun across the celestial meridian with the thief’s fate upon the crossroad gallows. The two riddles are not at all identical, but they do seem to be drawing upon the same themes and motifs.

”A thirteenth century illustration of a hanging during The Anarchy by Matthew Parris, from Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 016, folio 64r. Photo from Parker Library On the Web (licence: CC BY-SA 3.0)”

Line 4 and 5 explain that burning the lamp creates light. The riddle uses a word common in other riddle collections, but which crops up only once in Lorsch: viscera (“insides”). You can read my commentaries on Bern Riddles 11 and 32 for more examples of this. Perhaps this “burning of the insides” hints at the torture of criminals, which is occasionally mentioned in early medieval sources, although many of the more gruesome tortures that we might think of as quintessentially medieval date from the High and Late Middle Ages or the early modern period.

”The sun lights up the whitewashed walls of the pre-Conquest Priory Church, Deerhurst. Photo (by Chris Gunns) from Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY-SA 2.0)”

The final lines depict the lamp as if it were the dawning sun. The egregiam aulam (“excellent palace”) and the sacellum (“chapel”) are the church in which the lamp is hanging. In medieval literature, the world is often depicted microcosmically as a church, with the sky as its roof and the sun and stars as the lamps. For example, in his engaging, ninth century account of an anonymous monastery, the poet Æthelwulf describes the roof of his chapel thus:

Ut celum rutilat stellis fulgentibus omne,

Sic tremulas vibrant subter testudine templi

Ordinibus variis funalia pendula flammas.

[Just as the whole sky shines with glittering stars, so hanging ropes swing the quivering flames under the church roof in several ranks.]

Æthelwulf, De abbatibus, 623-5

We can also see this “church as sky” idea today, when we visit many churches and cathedrals and look up at the rich ultramarines and yellows that decorate their vaulted roofs and pagodas.

I do wonder whether the writer intended the riddle to have a hidden, allegorical aspect to it, where the lamp represents Christ in some way. Just like Christ, the lamp is not a criminal, but is treated as if it were one. Moreover, the dawning sun is often associated with the Second Coming of Christ, most notably in the Pauline epistles. Certainly, allegory in riddles is nothing new—in fact, Aldhelm is a master of it!

Anyway, I hope you enjoyed the riddle. I will leave you with the happy news that a burglar recently stole all my lamps. Why is this happy news? Well, it might have been a shady business, but it also left me completely de-lighted.

“VI Aethelstan.“ In Felix Liebermann, Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen. Halle: Max Neimeyer, 1903. Pages 173-83. Available online here.

Mattison, Alyxandra. The Execution and Burial of Criminals in Early Medieval England, c. 850-1150. PhD thesis. University of Sheffield. 2016. Available online here.

Marafioti, Nicole & Gates, Jay Paul. "Introduction: Capital and Corporal Punishment in Anglo-Saxon England." In Nicole Marafioti & Jay Paul Gates (eds.), Capital and Corporal Punishment in Anglo-Saxon England. Woodbridge: Boydell, 2014. Pages 1-16.

Tags: latin

Related Posts:

Bern Riddle 2: De lucerna

Commentary for Bern Riddle 10: De scala

NEVILLEMOGFORD

Date: Wed 13 Jan 2021Matching Riddle: Bern Riddle 10: De scala

Some riddles are more straightforward than others. But what about those riddles where it is not clear whether we are supposed to read them literally or figuratively? Well, this is one of them.

I have translated the title of this riddle as ‘On the ladder.’ However, it seems to be referring to a single rung or step, or perhaps the side-rail of a ladder. The riddle-creature explains that if she lived alone, then she could not go upon the directam viam (“straight path”). However, when joined with her twin sister—twin because they are identical—they allow everyone an iter velox (“speedy journey”) all the way to the top.

The riddle echoes several other Bern riddles. The opening line about “firm feet” (firma planta) recalls the “squishy places” of the extra-brilliant Riddle 4 and its eccentric horse-bench. Similarly, the closing two lines are reminiscent of the final line of Riddle 4, when the horse-bench explains that he dislikes being kicked. In this case, if the ladder is to be used, she must put up with having its feet stood on all the time. The “firm places” trope also turns up in the fish riddle, Riddle 30.

I mentioned at the start of this commentary that I am not sure how straightforward this riddle is. The question is whether the ladder just represents a ladder, or whether it has a deeper and more spiritual significance. On the one hand, there is no overt religious message in the riddle. It could be all about a very ordinary, bog-standard ladder. The riddle tells us that people use the ladder to reach what they want—perhaps the fruit or honey mentioned in nearby riddles. On the other hand, it might suggest the occasion in the Book of Genesis when the patriarch Jacob dreamt of a ladder or stairway leading from earth to heaven, with angels travelling up and down it (Genesis 28:12). In medieval exegesis, the ladder was an allegory for the path to heaven that the faithful must take, with the steps representing the piety, virtues, or ascetic struggles that led there.

I will leave you with this question: is the ladder supposed to be understood literally or figuratively? Or perhaps both? Is it is the kind of ladder you’d find in a shed, or is it an allegorical stairway to heaven.

References and Suggested Reading:

Grypeou, Emmanouela and Spurling, Helen. The Book of Genesis in Late Antiquity: Encounters between Jewish and Christian Exegesis. Leiden: Brill, 2013. Pages 289-322.

Tags: latin Bern Riddles

Related Posts:

Bern Riddle 4: De scamno

Bern Riddle 10: De scala

Bern Riddle 30: De pisce